Guest author Rachel Bensimhon is a Muhlenberg College senior and third year Digital Learning Assistant. Here are her thoughts on OER at Muhlenberg.

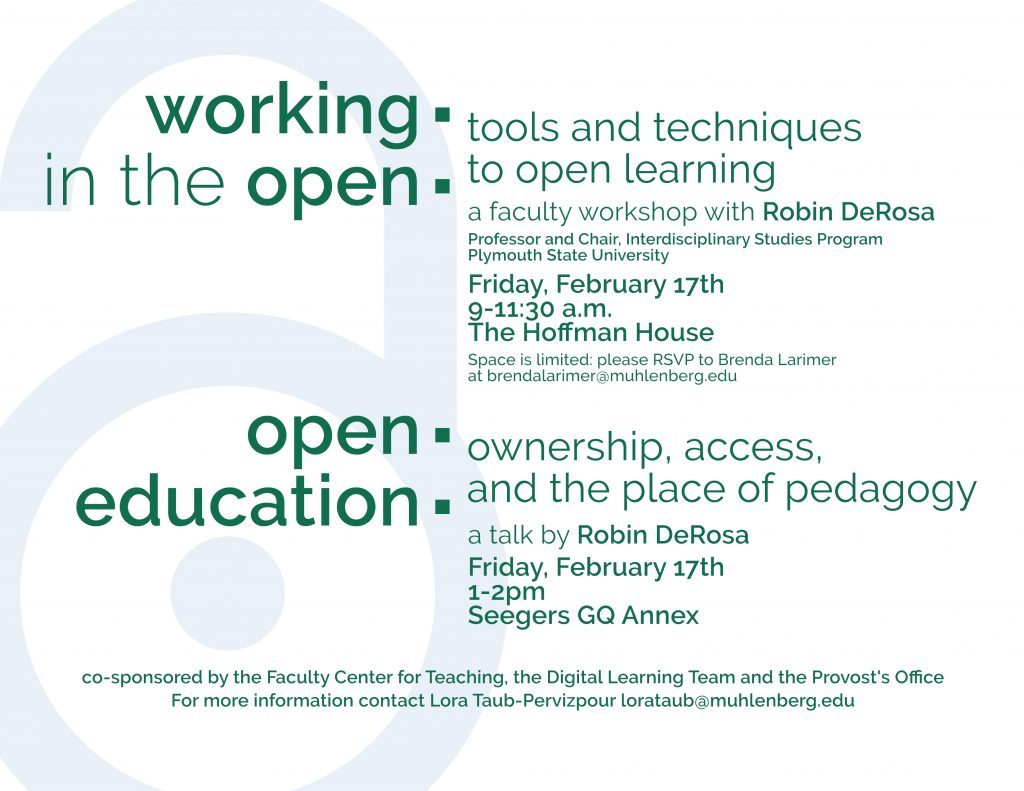

When I first joined Muhlenberg’s OER community as a sophomore/student representative in 2019, I wasn’t sure what to expect. When I thought about OERs then, my mind went to free textbooks/eBooks and online resources designed for open access and a “one-size-fits-all” approach. These are great in and of themselves. But as I attended more workshops and summits, I was pleasantly surprised to discover an entire world of OERs waiting beneath the surface.

OERs come in all shapes and sizes, and anyone can help contribute to them. They can be the classic archetypal free textbook or website, sure. But they can also take the shape of blogs with student-authored posts, or customizable PressBooks, or Wikipedia-style repositories of knowledge, or databases assembled through Omeka. I could go on! To me, OERs are creative expressions – transformative works rife with new possibilities for education. In looking to digital tools for OERs, we might expand the possible shapes that educational resources can take, and in doing so make them even more accessible and engaging for all learners.

Speaking of accessibility, OERs are highly inclusive and accessible. Not only do they allow for open access, they also allow for the expansion of authorship itself. Professors can make their own OERs, and students can contribute to their creation through their own writing, as well. In this way, OERs serve as a record of collaboration and knowledge-sharing, where unique perspectives can be made visible. When professors and students create and contribute to OERs, they add their own experiences and knowledge to the existing body of work.

On some level, I think OERs are gestures of openness and compassion – of storytelling. When I attend OER summits, I’m always struck by the level of care that goes into the work. From what I’ve seen, OERs are often born out of a desire to share knowledge with others from unique perspectives: to tell new stories in new ways, beyond the scope of traditionally-published textbooks/educational materials.

To me, OERs say, “I have this specific knowledge [of a certain subject area], and I want to share it with you, openly and in my own way.” And by bringing in multiple collaborators, that desire becomes “I have a story that I want to tell, and I want you to tell it with me, and together we might make something new.”

Digital tools, then, represent these “new ways” that stories can be told and knowledge can be shared. We might imagine an art history textbook as an online museum built with Omeka that anyone can visit, with metadata filled in by student contributors. Or we might envision a literature curriculum as a digital library powered by Zotero, where open texts can be read freely. As a DLA, these are only a sampling of the concepts that I want to help envision, facilitate, and make into a reality. These sorts of ideas are ones that we can envision through the possibilities that OERs have to offer. Through them, we might forge a more inclusive, accessible landscape, characterized by openness and compassion. And by advocating for open access, we can strive to build an equitable, engaged peer community where everyone can tell their stories.

Accessibility, inclusion, openness, care, compassion, storytelling: these are all ideals that OERs represent to me, and ideals that I want to facilitate through this work. I’m proud to be a member of a peer community that values these things!